What is BiD Challenge?

Business in Development Challenge, Utrecht, Netherlands

My BiD Story (for inclusion in the 2008 BiD Challenge book)

Time wounds all heels. And so my sense of nostalgia is again pricked as I recall how it was as a finalist in the very first BiD Challenge in 2005, and as a finalist again in BiD Challenge 2006, both in Utrecht, the Netherlands. On both tries I did not win, and in lieu of a prize I have prized pictures; instead of cash I have a cache of treasured memories of my perhaps-never-again opportunity to experience first hand the way of life of the Dutch, who are said to have created the Netherlands (while God created the world).

In the first BiD Challenge there were six Philippine finalists composed of two NGOs and an SME in the Non-Dutch-Organization Category and three indviduals, which included myself, in the Non-Dutch-Individual Category. The idea behind my entry was the use of carbide sludge, a waste product in the manufacture of acetylene gas, for making a construction material which can be used for building low-cost housing. And so it came to pass that in my category the jurors were more mesmerized with mushrooms from Suriname. To this day, each time I pass by an acetylene plant I think of the hundreds, perhaps thousands of cubic meters of carbide sludge simply stocked at the back of the factory slowly polluting the water table. All because May 2005, in Utrecht, was a month for mushrooms. A day after the 2005 Finals, all six of us Filipino finalists were treated to short drive-by tour of The Hague and then an Asian lunch by Philippine Ambassador to the Netherlands Romeo A. Arguelles, a welcome treat after a week of bread, cheese, deli meats and sour milk. A post-prandial chat in his official residence capped our memorable encounter with the amiable Ambassador. I had lunch with him again the following year.

It was 2006, and even as I was working for less pollution and more low-cost houses, I was also into non-circulating hydroponics – the growing of plants without soil and pumps that consume electricity. This farming method that can squeeze watercress out of stone (as well as lettuce, pepper, tomatoes, melons and many others) now sprouted a new branch applicable to those with little capital. I teamed up with the National Federation of Cooperatives of Persons with Disability-- started training their member cooperatives and formalized a joint business venture where my own version of the technology which I called Simplified, Non-circulating Hydroponics (SiNcH) will be used to produce high-value vegetables as a livelihood project. The project needed money, so perhaps we could try our luck in BiD Challenge 2006. This time BiD Challenge was run first on a country level in cooperation local partners – first in Peru and the Philippines. But the finals in Utrecht had no more categories; each country winner, 25 of them, will vie for prize money available only for 16 finalists. My entry in partnership with the NFCPWD -- “Production of High-value Vegetables Using Simplified Non-circulating Hydroponics” -- was declared Philippine Country Winner. For the second time, I went to the Netherlands. For the second time I did not win. And for the second time, it was not winter and I missed another opportunity to see, feel, and taste snow.

Shortly after the BiD Challenge 2005 finals, John Van Duursen, came to Manila in preparation for making the Philippines the first country-level BiD Challenge 2006 “Hotspot” along with Peru. Together with fellow 2005 finalists Joshua Guinto, Robert Sagun, and Noel Percil we brainstormed with John in a Quezon City hostel where for a possible lead partner the Philippine Business for Social Progress came out the consensually most favored suggestion. John came back after a few weeks, and met in Bacolod with the PBSP local chapter. It was a Friday and after days of tiring work all he wanted was to be in a quiet, gezellig place away from the city. That sounded like our humble home and so John Van Duursen, co-founder of FairVentures and BiD Network Foundation, hung loose for two days in our sleepy, fourth-class coastal town in northern Negros; jogged along its coconut-lined beach road, quaffed nighttime San Mig lights by our porch, shared a seaside pool with adoring teenagers, and solved my puzzlement as to why the Dutch, as I observed in 2005, greet each other with a single kiss, yet at times two, and on other occasions, three alternate pecks on the cheeks . I was not able to make him eat “balut,” but he liked our version of “daing” which we call “lamayo,” tenderer than the former and unsalted and sunned for only half a day, which he likened to soused herring, a Dutch delicacy typically eaten raw with onions. One man's cooked duck egg is another man's raw fish slice, yet lekker to both.

On both BiD Challenge Finals I was fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to the Dutch countryside, to a dairy farm in the northeast and the windmill village of de Zaanse Schansin at the edge of the Zaan River in 2005, then to a peach farm in Ijsseldijk to the west near the German border in 2006. On the road I was immediately awed by the flaaatness of the country (I never saw a natural mound more than a meter high). Conspicuous by their absence were the advertising billboards except for a few small ones offering, for example, building leases. Noticeable too were the vehicles that never seem to honk (which was true even in the cities, a form of politeness for them). Not only that, but Netherlands ain't France, and I could get by with English for everything, guilt free. Yet even in the far outdoors I still got the feeling that this was a crowded country, as in fact it is, packing 482 persons per square kilometer.

While the old buildings, especially in Amsterdam, draw out reverence for their tenacity and history, the modern structures were equally impressive. Each one has something unique, each one seemingly in an architectural one-upmanship with the others. The interplay of form, color, and materials gave me the impression of massive artworks only incidentally used as dwellings or offices. The element of artwork as deliberate ingredient of city life was most noticeable in The Hauge (Den Haag), the seat of government, where one can encounter massive outdoor sculptures at almost every other turn. Our visit to the ING Bank Head Office in Amsterdamse Poort in 2006, was a highlight: ten towers of varying heights with hardly any wall vertical and clad with handmade bricks, plus inside, large-format paintings on both sides of a long central corridor. Their giveaway coffee-table book of their art collection is indeed a treasure.

One of the best places for me to observe the locals was the train station. Claims that the Dutch are standing out as the world's tallest people seemed to be borne out as true here, as well as the reported trend of an increasing percentage of population from foreign extraction. Yet some elements can be incongrous, for example ladies with black veils and BlackBerries, a Dutch rollmop of Islamic conservatism and Western consumerism. There were many other places I have wanted to visit, but time and Euro conspired to limit my gallivanting. Yet those places I managed to visit within a tight schedule and tighter budget remained special and unforgettable: the Amsterdam canals (reputed to be the most beautiful way to see this capital city), dinner at De Waag (the Weighhouse, a remnant of the former city walls), Vondelpark, Ameerfoort (birthplace of Piet Mondrian), the Rijksmuseum with its Rembrandts.

Would I forget the stroll through the Red Light District at dusk when the curtains of the glass windows begin to undraw, and the commerce of man (and woman) begins, lucky enough to have started sauntering up the Oude-zids Achter-burgwal canal, crossed the bridge at the end and came back the other side, therefore passed a string of hard evidence with names like Hash Museum, Casa Rosso, Banana Bar, Absolute Danny, that proved that the Dutch are the most liberal-minded and the country is run as much for the people as possible. Most of the working girls are not really Dutch, but Eastern Europeans, many trapped in debt and drugs but as many in control of their destiny. A Dutch told me that, of course. And if this isn't enough proof that laissez faire works then the fact that everything that comes out of the tap in the Netherlands is potable, should. Fortunately I never had any waiter telling me water from the tap is not fit to drink because he would rather have me pay for bottled water instead, because then he would be a lying bastard.

That I still lost on my second try was not at all a letdown for me after a short while, after all, this was a competition where there would be winners and losers. In addition, reaching the finals twice in a row was an achievement in itself, albeit one that did not come with prize money. In 2005 I was up against close to 800 other participants; in 2006 it was 1,600 contestants from 94 countries. I got to travel to the Netherlands twice in a row, stay for one week all expenses paid and with a daily allowance to boot. Nonetheless, the basis that my two jurors used to drop my entry still feels iffy to this day. That I will not be growing the produce directly (this will be done the beneficiary persons with disabilities) but be involved as technology provider and partner did not sit well with them, seeing my role in the business as peripheral even as this setup will enable the business to grow rapidly and help as many PWDs faster while generating revenue for myself as well. This fits right into the spirit of entrepreneurship for me, because he who everyday is up to his neck in the business of his business is just in business. An entrepreneur sets up a business that runs with a minimum of intervention, giving him time to start more businesses in the same manner, and more important, time to get a life.

Today, my efforts to start up a simplified hydroponics business continue, with an American partner who found his way to my BiD web page and believed a hundred percent, unlike some Dutch, in my quest to have the world feed itself using nothing but some plastic pots and mineral salts. After all, as recent events bear out, we can't be importing our food from China, can we? I look back a lot at the events of 2005 and 2006, in certain way as inspiration, in another as challenge to make good. Like the Dutch say “Wie het verleden niet eert is de toekomst niet weerd.” (Those who don't honor the past are not worthy of the future, something like that.)

After pancakes, an afternoon stroll

The first group photo of the finalists, with the organizers, in the 2005 (and the first) BiD Challenge. Among others, the finalists were from India, Bolivia, Suriname, Vietnam, Rwanda, and of course there were six of us from the Philippines.

Checking in

The BiD Challenge 2005 finalists were billeted at Hotel Mercure at the outskirts of Utrecht.

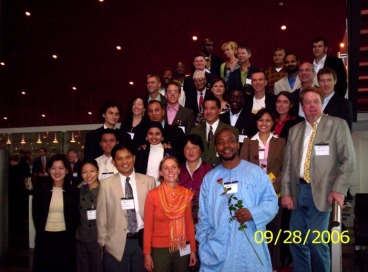

2006 Finals

The top 25 finailists (screened from several hundred entries from 94 countries) in the 2006 BiD Challenge pose with the organizers during the Awards Day at Rabobank, Utrecht.

Pinoys in The Hague

2006 BiD Challenge Filipino finalists pose with Philippine Ambassador to the Netherlands Romeo A. Arguelles in his official residence in the Hague. From left, Joshua Guinto, Noel Percil, myself, Ambassador Arguelles, Jonah Nobleza, Daryl Napasundayan, and Robert Sagun.